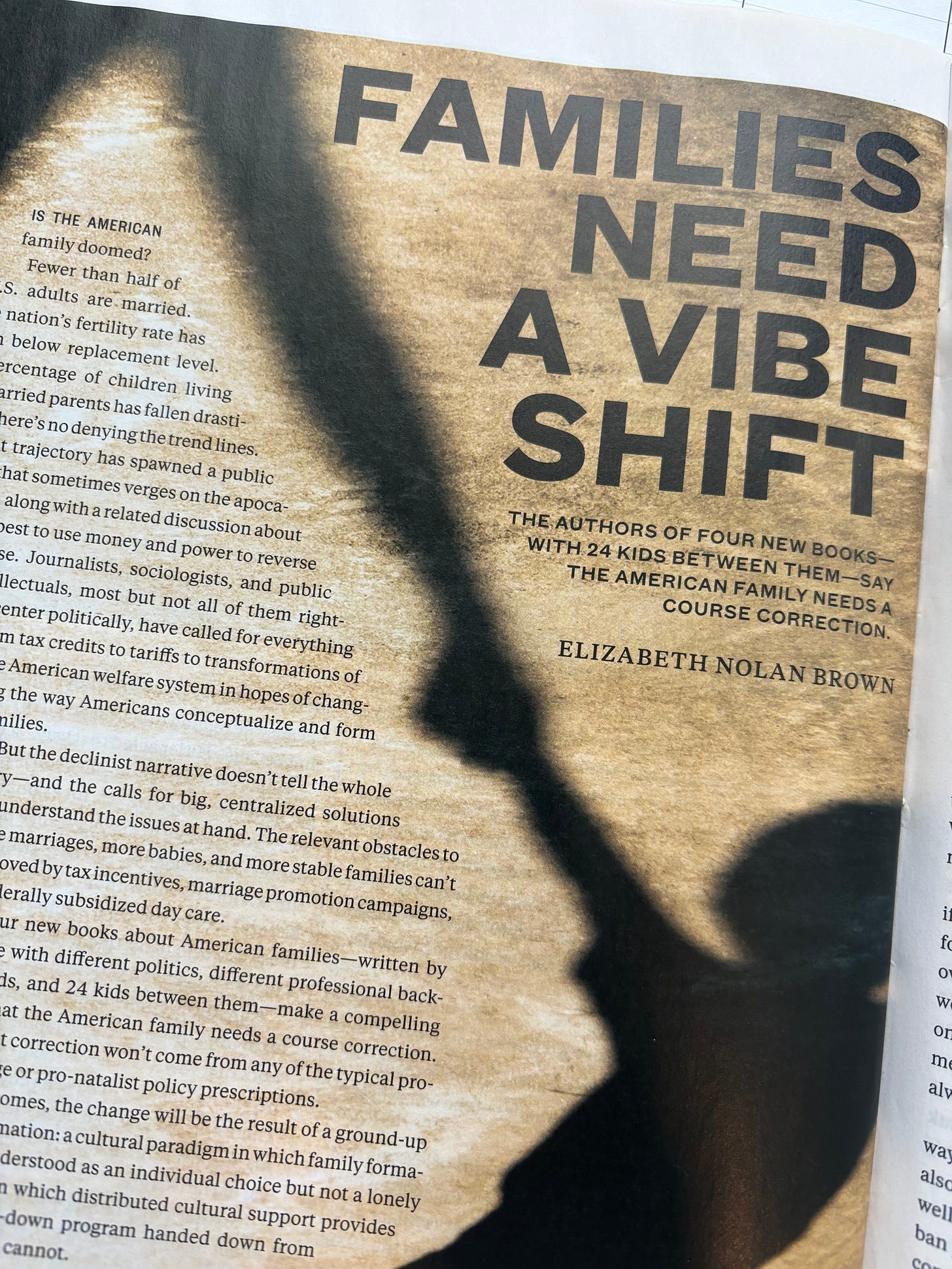

So, I read a bunch of books about American family life — marriage, birth rates, parenting — and wrote up my takeaways for Reason's latest issue.

My favorite of these books was Tim Carney’s Family Unfriendly: How Our Culture Made Raising Kids Much Harder Than It Needs to Be. "Someone has convinced us that parenting should involve much more effort than any generation before us put in. That is madness," writes Carney.

I'm only slightly joking when I say this book has made me a pro-natalist…

Pro-natalism tends to be filled with 1) tech weirdos, 2) sexists, 3) perfectly fine people with delusional ideas about what will influence birth rates.

Carney falls into none of these categories. His ideas about how to make family life better (and possibly convince more people to have children as a side effect) span the gamut from zoning reform to less paranoid parenting to rejecting travel sports teams, but most fall firmly outside the territory of "big government program" or “nationwide initiative” or "just throw money at the problem."

I don’t know if the changes he recommends would really boost fertility rates—maybe at the margins. But that’s not particularly his point, anyway. He wants American cultural changes that will make life better for existing (and future) families, and to convince people uncertain about having more kids or having them at all to not feel like everything is stacked against them doing so. Much of his book focuses on the structure of American neighborhoods (and the dumb laws that keep them that way), the pathologies of modern parenting, and the ways various parenting expectations are making parents and kids miserable and mentally unsound.

(Carney is also just a really crisp and entertaining writer, who offers sentences like “if you want fecundity in the sheets, you need walkability in the streets,” and: "Raising kids is a bit like smoking pork shoulder: it's not going to be quick, and you do need to check the thermometer from time to time, but you'll get the best outcome if you avoid constantly lifting the lid and prodding the meat.")

Eschewing conventional wisdom about fertility decisions is also the big strength of Hannah's Children: The Women Quietly Defying the Birth Dearth. For the book, author Catherine Ruth Pakaluk—a Catholic University professor and mother of eight—interviewed a bunch of college-educated women who intentionally had 5 or more kids (sometimes twice as many or more).

Going in, I was expecting something preachy and gratingly regressive. But the book turns out to take a really fascinating, anthropological look at the lives of a group of women who frequently fall outside of our preconceived notions of “woman with a boatload of kids” looks like. And Pakaluk’s analysis, while definitely sympathetic to her subjects, is anything but a Phyllis Schlafly-style plea for women to stay in some imagined traditional sphere. Pakaluk is very attune to the kind of tradeoffs that having any, and especially many, kids requires for modern women, and examines both the positives and the negatives in the lives of women who decided to tip the scale in the balance of big families.

Hannah's Children is also a very libertarian book. Pakaluk comes to many of the same conclusions as Carney about economic incentives not being able to move the needle here (which is something I wrote about at length in Reason last year).

(This is not to say that having more money or better childcare or whatever wouldn't make life easier for some existing families, just that a lack of resrouces is not actually the big thing stopping people from having any or more children.)

For the women Pakaluk interviewed, "the relevant obstacle to choosing a child … was the cost of missing out on the other things you could have done with your time, your money, or your life." In short, it’s about opportunity costs.

From my Reason piece:

This calculus makes birth rates "very difficult to reverse using the standard policy levers," writes Pakaluk, noting that her subjects' stories "sorely challenge family policy prescriptions, particularly pro-natalist policies. Cash incentives and tax relief won't persuade people to give up their lives. People will do that for God, for their families, and for their future children." Having children—and especially having a lot of children—is fundamentally a private, personal commitment.

In a culture trending less religious, fewer people will find God an acceptable arbiter of their family size. Notably, Pakaluk writes that although 100 percent of her sample was religious, big families here weren't founded on religious objections to birth control. If birth rates are to rise, more people must want kids or a big family for their own sakes.

Kids might be understood as experience goods—goods "whose total costs and benefits cannot be fully assessed in advance," as Pakaluk puts it. This makes it hard for those without them to know what they're missing.

Moreover, highly educated professional women spend many years working toward other goals. "Each year that they enjoy their studies, training, or work reinforces the value determination that having a child will mean giving up things they know and love, for an unknown quantity."

The two remaining books that I wrote about cover similar territory. Both Melissa Kearney’s The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind and Brad Wilcox’s Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families, and Save Civilization focus on declines in marriage rates and potential drawbacks therein, especially as it pertains to families.

A recurring theme in both books is the fact that marriage broadly, and marriage before kids, is becoming a class-segregated phenomenon.

Kearney points out that in 2019, just 63 percent of U.S. children lived with married parents, down from 77 percent in 1980—a drop of 14 percentage points. But for mothers with a college degree, the drop was just six percentage points, from an already high 90 percent in 1980. Meanwhile, for mothers without a college degree, the drop was 23 percentage points. These days, only 60 percent of kids whose moms have a high school but no college degree now live with married parents, and only 57 percent of kids whose moms have no high school degree do.

Higher income and college-educated folks are now more likely to marry, more likely to raise their children within a marriage, and less like to divorce than their lower income or less educated counterparts. Wilcox’s book takes some stabs at blaming this on “elites” who “talk left” but “walk right” themselves when it comes to marriage and family. To me, these were the least convincing parts of Wilcox’s book—ascribing a sort of power to entertainment products and elite media that I just don’t think exists. (There are all sorts of reasons why lower income people might be less likely to marry and/or to have kids within marriage today, but I don’t think divorce-friendly Atlantic articles are one of them.)

Still, I think the underlying phenomenon here is one worth paying attention to. It’s also a phenomenon that may not be moved by traditional financial incentives of the sort people immediately jump to when this is discussed, however. For instance, Kearney's research found that boosting men's incomes (and theoretically their "marriagability") did not boost marriage rates, though it did boost birth rates among both married and unmarried couples.

Both the Wilcox and Kearney books were interesting reads, full of good data and reasonable recommendations (and neither the sort of reactionary screed that their critics sometimes imagine). But, ultimately, I found some of their core arguments unconvincing. When it comes to positive outcomes among married people, or the kids of married people, it’s impossible to separate the fact that they are married from a million other variables.

Maybe married people are richer and more fulfilled because they're married—or maybe they're married because they're richer and more fulfilled. Most likely, it's a constellation of factors. But the fact that married people are on average happier does not mean everyone would be happier married.

Likewise, it's hard to detangle correlations from causes when it comes to the well-being of children raised in different family structures. Two-parent households differ from single–parent households in many ways, including the fact that they're more likely to have two incomes and, thus, less likely to be in poverty. It's impossible to know how much of the benefits that accrue to kids of two-parent households come largely from the marriage aspect, the financial aspect, or some convoluted combination of attributes.

Two-parent households are also associated with more educated, older, and wealthier parents, which can mean everything from better schools to more books in the house, more nutritious food, and more money for enriching activities. Children of single parents are more likely to be black or Hispanic and less likely to live in safe neighborhoods. Marriage can be a proxy for religiosity. It may also be correlated with emotional stability, as well as other traits that could influence child outcomes. And let's not forget genetics—some heritable tendencies may make someone less likely to marry and also less likely to have offspring with traits that set them up for certain sorts of success. Marriage, or stable cohabitation, is a proxy for all sorts of other advantages, which means that even if it were somehow possible, simply marrying off single parents would go only so far.

Neither Kearney nor Wilcox deny that there are a lot of variables and influences at work here. But I found both a little to quick to wave these away, or to interrogate their influence in depth.

Let’s take the finding that kids raised in single-parent (generally single mom) households are more likely to face disciplinary action at school and to be in trouble with the law. A lot of folks jump immediately to “kids need two parents!” and especially “kids need a dad!” But we know that schools can be more likely to respond with harsh disciplinary action to children of color, especially black children, and that our criminal justice system can be racist, classist, and biased against immigrants. How much might those factors—combined with the fact that lower-income, black, and Hispanic children are more likely to be raised in single-parent households—explain some of the discrepancy here?

For basically every finding of uneven outcomes among the children of married and unmarried parents, there are myriad plausible explanations that we’d be wrong to discount or ignore.

That’s not to entirely dismiss the idea that kids may be better off with two parents — or at least two (or more) familial or close adults — around. I’m currently raising a toddler and a baby, and I can’t imagine doing it alone. When my husband is out of town for any length of time, I lean heavily on other family members (thanks, mom!) and still wind up with less sleep, less patience, less thought-out meals, and a messier house, among other things.

It’s complicated, is the unsatisfying but most realistic thing you can say here. I don’t think we should dismiss concerns like those aired by Wilcox and Kearney, but I also think we should avoid falling into a trap where we see marriage as some sort of silver bullet.

If you want to read more from and about these books, go check out “Families Need a Vibe Shift,” from Reason’s July 2024 issue. I also recommend that folks interested in these issues from a policy or cultural perspective pick up any of these four books, and especially that parents or people contemplating becoming parents read Family Unfriendly.

As a married (29 yrs this month) mother to 4, who also homeschooled, I can say that this lifestyle choice was not easy. My husband and I both had college degrees but we knew, before we were married that we wanted a large family and we wanted them to be homeschooled. We were prepared. Financially it was rough but we did it.